In the previous article, we look at how the tech industry is reshaping the way companies are structuring themselves. Today, we look at a particular example, Zappos.

Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh made the announcement that the company was to shift to a holacratic model in 2013. This transition was sped up in 2015 as the management system was finally overhauled. Google this topic and Zappos and you will see that a lot has been written on this, with countless critical articles appearing less than 12 months after the switch. But what is holacracy and how does it function?

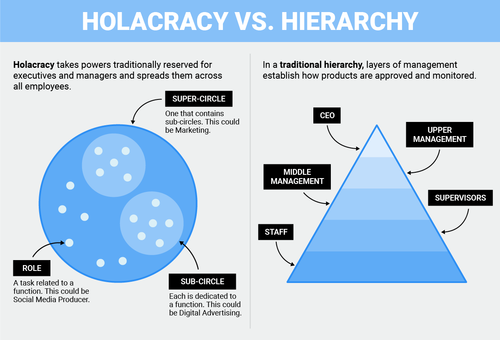

Let’s start with the basics. In their own words: Holacracy is a comprehensive practice for structuring, governing, and running an organization. It replaces today’s top-down predict-and-control paradigm with a new way of achieving control by distributing power. It is a new “operating system” that instills rapid evolution in the core processes of an organization.

In a city, people and businesses are self-organizing. We’re trying to do the same thing by switching from a normal hierarchical structure to a system called Holacracy, which enables employees to act more like entrepreneurs and self-direct their work instead of reporting to a manager who tells them what to do. This use of a city to illustrate their vision for how a company could reorganize and restructure is an interesting one as we have mentioned in the previous article that when cities grow, they become more productive. When companies grow, that same pattern doesn’t appear.

The basic premise of Zappos’ holacracy experiment is that there is something wrong with existing business structures. They have diagnosed a productivity problem at the heart of traditional companies. As they can see cities out-achieving companies in the relationship between growth and productivity, they have aimed to mimic certain structures and relationships found within cities. This diagnosis is reliant not just on identifying the disparity between city growth and business growth, but also on what specific features give cities the advantage.

Zappos have identified individual autonomy and its resultant entrepreneurialism as being at the heart of this performance success. Hence why they have looked to prioritize these features in their business. And to achieve that, they look to technology, naturally. Through the use of technology, it is possible to centralize elements of communication and organization. The difficulty is making that system work effectively. An open task marketplace where people can look at available work and gravitate toward tasks they want to participate in allows people to focus on the kinds of tasks they feel most motivated to do. This is part of Zappos’ overall wish to identify the strengths of each individual and utilize them as well as possible.

However, this begs the question: What about the unglamorous tasks? What about the jobs which don’t require entrepreneurialism but instead need simply time, effort, and dedication? Zappos’ approach to this is that different people want different things. Some people enjoy structure and consistency and within Zappos these people will gravitate towards the kinds of tasks and roles which deliver these ends.

This variety is an important part of the overall concept. Different teams will use different processes, and those processes should evolve naturally out of the fulfillment of that task by the individuals performing that task. A slight example is given in how Zappos interact with meetings:

Meetings happen when they need to happen on whatever cadence makes sense. So some groups meet frequently, some groups meet very infrequently. And so, just like in a traditional organization, meetings happen when they need to.

Forbes report that Zappos’ employee turnover rate for 2016 was the lowest rate they had experienced since the company was founded 18 years ago. At the moment, this is the strongest evidence we could ask for to dispute claims of a trend.

In future articles, we will continue to look at how other tech companies are bucking the trend of traditional organizational structures.